Date: September 11th, 2017

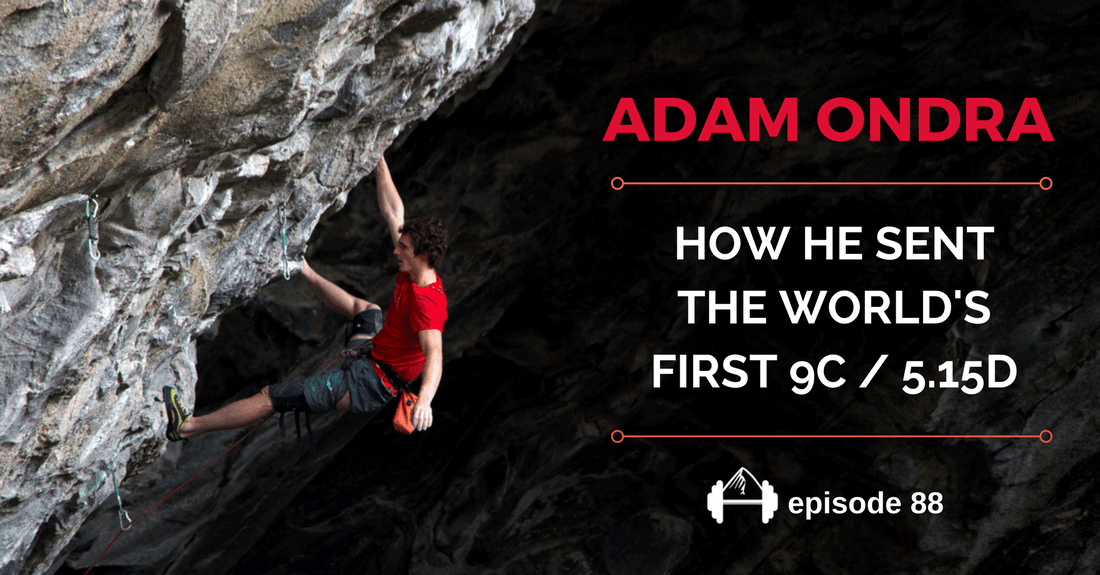

About Adam Ondra

Adam Ondra is debatably the best climber in the world, or is it even debatable anymore? He just sent his long-term project, Silence (9c/5.15d) in Flatanger, Norway, which is the first 9c in the world. Adam was also the first person to send 9b+/5.15c when he did Change in Flatanger in 2012. Since then he has done two other 5.15c’s: La Dura Dura in Spain and Vasil Vasil in the Czech Republic. At the age of 24 and just out of university, he has sent more hard rock climbs than any other climber by far. Here’s what his Wikipedia page has to say about him.

Sport Climbing Accomplishments

As of 7 December 2014, he climbed 1,162 routes between 8a (5.13b) and 9b+ (5.15c), of which 3 were at 9b+ (5.15c) and 548 were onsights, including 3 onsights at 9a (5.14d) and 15 onsights at 8c+ (5.14c).

His bouldering accomplishments include hundreds of boulders between V11 and V16. He’s also a record-setting comp climber, and just placed 2nd at the IFSC’s Arco World Cup last month in between trips to Flatanger. From his wikipedia page…

Competition Climbing Accomplishments

He is the only athlete to have won the World Championships in two disciplines, lead and bouldering. In addition, he won both medals in the same year, during the 2014 edition. He also has a similar record in the World Cup, being the only athlete to have won the World Cup in two disciplines, lead in 2009 and bouldering in 2010.

And you know that saying, “Find your Dawn Wall”? Well, he found his Dawn Wall: it was the Dawn Wall and he sent it in just a few weeks. Also from his wikipedia page…

Dawn Wall

On November 21, 2016, Ondra completed the second free ascent of the 5.14d (9a) The Dawn Wall, in Yosemite Valley, California. The route is widely regarded as the hardest big wall in the world. Ondra was also the first person to lead every pitch.[15] The first free ascent was completed by Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson in January 2015.

Adam’s Unbelievable Moves of Crux 1 on Silence

When I watched Adam do the moves of the first crux on Silence, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Both his climbing style (fast and intense) and the actual moves he was doing were like nothing I’ve ever seen. I know they’re making a film about this route, but here’s a teaser of those moves.

Adam Ondra Interview Details

It was an honor to interview Adam for the second time on the podcast yesterday (listen to our first interview here) at the farmhouse where he’s staying in Flatanger, Norway. I’ve been here in Flatanger for the past couple weeks and we’ve been lucky enough to watch Adam climb on Silence and his new projects. I wanted to ask him how he trained for Silence, what the process was like, and just learn a little more about him.

Here’s what we talked about:

- Why he named his 9c Silence

- Why he thinks it’s 9c

- Kneebar training and new kneebar tactics

- Why he climbs so quickly

- How he’s gotten so much bigger

- If the added muscle weight has affected his climbing

- What he eats and why

- What he’ll do next

Adam Ondra Links

- My first interview with Adam in 2015 about his training and the prospect of 5.15d

- Adam’s website: www.adamondra.com

- Adam on Instagram: @adam.ondra

- Adam on Facebook

Training Programs for You

Do you want a well-laid-out, easy-to-follow training program that will get you stronger quickly? Here’s what we have to offer on TrainingBeta. Something for everyone…

- Personal Training Online: www.trainingbeta.com/mercedes

- For Boulderers: Bouldering Training Program for boulderers of all abilities

- For Route Climbers: Route Climbing Training Program for route climbers of all abilities

- Finger Strength : www.trainingbeta.com/fingers

- All of our training programs: Training Programs Page

Please Review The Podcast on iTunes

Please give the podcast an honest review on iTunes here to help the show reach more curious climbers around the world.

Photo

Photo by Neely Quinn of Adam Ondra on Silence 9c/5.15d in Flatanger, Norway.

Transcript

Neely Quinn: Welcome to the TrainingBeta Podcast, where I talk with climbers and trainers about how we can get a little better at our favorite sport. I’m your host, Neely Quinn, and once again I am coming at you from Flatanger, Norway, where I’ve been for the past few weeks. We’ve been following Paige Claassen, who we are here with, on her project Odin’s Eye, which is a 14c or 8c+. That’s been super fun- I’ve been podcasting about that. Her climb is right down the hill from Adam Ondra’s project Hard, which he has now named Silence, because he sent it last week. I really wanted to talk to Adam about his projecting process, how he trained for Silence, and just to get to know him a little bit better, because he is a super interesting guy and he is a very unique climber. His style is different than anything I’ve ever seen- he is a very fast climber, he is very precise, he uses momentum a lot, and so it’s not like anything I’ve ever seen, to watch him climb.

Silence is the first 5.15d, or 9c in the world, so congrats to him for that. He also was the first person to climb 9b+, or 5.15c, and he has climbed three of those now, so he decided it was time to work on something harder. That brought him to Flatanger, where there are plenty of projects for him. He told me that there are a lifetime of projects for him here, so that’s saying quite a bit. In this interview I talk to him about all these things, and hopefully it gets you to know Adam a little bit better.

Before I get started with the interview, I want to remind you that if you want help with your own training, that’s what we do here at TrainingBeta. If you go to trainingbeta.com and go to the top where it says “training programs”, you are going to find a lot of programs in there for people of all abilities, including training programs for boulderers, some that are just for route climbers, and people who just want to train power endurance or finger strength- there is something for everyone in there. So trainingbeta.com, and hopefully those programs will help you reach your goals just like Adam has.

Without further ado, here is Adam Ondra. Enjoy this interview.

Neely Quinn: Alright, thank you very much for talking to me today, I know you are really busy. Welcome back to the show.

Adam Ondra: Thank you.

Neely Quinn: I’m just going to jump right in, and say congratulations on sending Project Hard.

Adam Ondra: Thank you.

Neely Quinn: So how are you feeling about that?

Adam Ondra: Well, it’s already been a few days, but it still feels like something very fresh. That’s probably because it was so important, and so intense, and so powerful.

Neely Quinn: Have you had that before, where projects you’ve finished them, and you feel sort of elation, for days on end? Or is this something new?

Adam Ondra: Like for sure, the Dawn Wall was special. But I think the more you invest into one single go, and the more the actual sending takes, then it takes longer to enjoy this moment of victory [laughs]. So like the Dawn Wall doesn’t only take a lot of time to work on it, but the actual ascent takes eight days. And even this took a lot of time to work on it, but the actual ascending is relatively long as well, like twenty minutes. For me, sometimes if it’s a boulder problem that I might work on forever, but then because it’s like ten seconds of effort, it can feel a little different, and more, maybe short lived.

Neely Quinn: So is this the longest thing that you have worked on?

Adam Ondra: Yeah, this is by far the longest I’ve ever worked.

Neely Quinn: First of all, tell me about the route. Can you describe it for me, and are you sick of talking about this yet?

[laughter]

Adam Ondra: Well, I’m maybe sick of talking about it to mainstream media, where I have to explain everything. For climbing nerds it’s much easier [laughs]. So the route is maybe forty five meters long, sixty degrees over hanging, and this [unclear] is just really, really, really bouldery. All you need to do to climb this is hard boulder problems, and have a certain level of fitness so you can climb the easier sections, get a good rest in the kneebar, recover as much as problem, and the just do heinous boulder problems. Those ten moves, the crux one, is by itself possibly the hardest boulder problem I’ve ever done. For sure it is like an 8c/v15 boulder. It took me four trips to just link those ten moves together.

Neely Quinn: Really. Four trips, how many days?

Adam Ondra: I don’t know, like every trip was maybe two weeks, so… And I literally worked on it like a boulder problem. I just jugged up there and worked it as a boulder problem. Maybe sometimes I would go higher and work on crux two and crux three, but crux one was the real nightmare, the real crux of the route.

Neely Quinn: Right, yeah.

Adam Ondra: And of course, so much time of those four trips took me actually to just figure out the beta, because it’s just so unlikely that you would climb it this way, but I’m pretty sure this is the easiest way to get up. There are some maybe different betas, but in my point of view they’re even harder.

Neely Quinn: The upside down crack moves?

vYes. I had the beta how to not climb it upside down, how to climb with my hands first, but I just found it much harder.

Neely Quinn: Have you ever done anything like those moves before?

Adam Ondra: Not even in a gym. Or the only moves I did similar to this would be simulations that I would set in my own gym [laughs].

Neely Quinn: Okay, nice [laughs].

Adam Ondra: But that’s it.

Neely Quinn: So how many pitches is this route technically?

Adam Ondra: I mean, the first twenty meters is 8b, up to a really huge kneebar. Then you would climb a bit more, which is not so hard, and then ten moves v15, good rest in a kneebar. It’s a good kneebar, or now I can see it as a good kneebar, but last year I could hang for maybe fifteen seconds with no hands. Now I would be hanging for like four minutes. I think that was the key, that I not only worked on my climbing abilities but also my resting abilities- that was the key. Above there, there is five moves of v13- a hard undercling move and really high step. The last crux to finish it up is v10, or something like that. Really low percentage, kind of. Not so hard, but easy to mess up.

Neely Quinn: So there’s a lot of cruxes in a lot of places to mess up.

Adam Ondra: Yeah, but in the end, what makes it so difficult, is the crux one. The rest of it is like… to get there is just something that makes me a little tired, and what is above is more to not mess up. If you had the level to do the crux one, with the previous climbing, then it’s very likely that you are going to send it, as long as you have the crux two and crux three wired. If the top of the route was after the crux one, it could still be possibly 9c, even though you’re still facing v13 and v10 boulder problem. But of course there is this kneebar. If there was no kneebar, then we wouldn’t be talking about 9c, but 10a, and that’s something that I would never, ever have the level to do.

Neely Quinn: Really?

Adam Ondra: No, no way.

Neely Quinn: What about 9c+?

Adam Ondra: I don’t have the level to do 9c+, that’s for sure. Not right now. I mean, maybe one day, but I need to be so, so, so much stronger.

Neely Quinn: So you think this is the tippy top of where your fitness is right now?

Adam Ondra: Oh, hell yeah. There is not really much difference whether you are working on a route for twenty, hundred, or two hundred days. If you don’t have the level to do it, you’re probably not going to do it, even if you invest so many more days. Let’s say after maybe fifteen, twenty days of work, there is not so much more you can work on. Unless it’s maybe such a route as Project Hard, or Silence, let’s call it.

Neely Quinn: Right, yeah, and you did. I saw that you named it Silence. Can you tell me why?

Adam Ondra: It’s because of this weird experience I’ve had on the Project Hard. Most of the hard routes that I did, I would be just like, screaming a lot, while doing the crux moves. But those moves are pretty special, and it’s kind of actually hard to do those moves while screaming, because they are so much about precision. Once you scream, you are kind of like, made moving with your body a little bit too much. While I was actually entering the crux one- because this whole route is kind of like focus into relaxed kneebar, focus into relaxed kneebar, and focus into relaxed kneebar.

Then there is the crux one, which has a bad kneebar right under the crux one, which is like a really bad kneebar. Maybe ten, fifteen seconds no hands, and then I go. And I have to be 100% relaxed in the last ten seconds of the kneebar, and then I would have to switch on fighting mode, because it starts right there. The first three intro moves are already v11, and then move number four is probably the hardest single move. It’s really hard from two compression side pulls, it’s really hard to just hang on there with a really shitty foot, to make a stab into a left hand fingerlock. That is the move where I always thought that I have to be 100% focused, two seconds switch into the warrior mode.

Sometimes I just made mistakes, and I made it to this crux move still being kind of relaxed, and somehow I was so lucky, and so precise that I still could do this move in relaxed mode, without screaming, without anything. I thought it was just pure luck, maybe it was just relaxed, or I don’t know what happened, but I somehow made it through this crux move. Then it was on, and I was like “Ooh, I’m so good there, I’m not tired at all, and I have to finish the crux one off”, and that’s what I did. What I felt during this crux one, instead of warrior mode, was more like just silence.

Neely Quinn: And that’s how you felt when you actually sent it?

Adam Ondra: Yeah that was the sending try. Of course then I was in a kneebar, I was there for maybe four minutes. I knew I was pretty fresh, and of course I got really tired and really nervous, because then it’s only crux two and crux three. I know I would do the route starting twenty meters in, being in that kneebar and in a way worse state, so I knew I could do it. It was just a question of not freaking out. I was definitely nervous- some of the moves were maybe not so good. But then I made it to the top, and I somehow reached the anchor, and there was silence again. I was kind of expecting that I would just scream of joy and victory and excitement, but all of this kind of got stuck halfway through, and I just couldn’t do anything. I was just hanging on the rope, and all I could feel was maybe tears in my eyes, but nothing came out of me.

Neely Quinn: Has that ever happened to you before?

Adam Ondra: No, nope. This was so special.

Neely Quinn: Why was this one so special?

Adam Ondra: I have no clue. For sure it’s a route for which I have sacrificed the most, trained the most, and it has been stuck in my mind for a long time, so that’s probably why.

Neely Quinn: Nice. So how long have you been working on it?

Adam Ondra: So I bolted it in 2013, but back then I thought it was just a bit too hard. I knew it was possible, but I just abandoned the project. Then in 2016, in the spring, I tried it again, and it somehow seemed more realistic, so I started working on it. Pretty much during the summertime I was either here in Norway working on the route, or back and home and training specifically for that.

Neely Quinn: So you haven’t been doing anything else?

Adam Ondra: Last year, between the end of May until August, and then this year from May until now, until September.

Neely Quinn: Okay, and you’ve come here how many times?

Adam Ondra: It was like seven trips in total. An average was like two, three weeks. Last trip this year was maybe one month and ten days I think.

Neely Quinn: Okay. Yeah, that’s quite a lot. How many days do you think you’ve spent on the route?

Adam Ondra: I haven’t really tried to count. Maybe sixty, seventy?

Neely Quinn: So you don’t really keep track of this kind of thing? When you said that you didn’t even do the hardest moves on the route for the first four trips-

Adam Ondra: I did the hardest moves, but I was trying to link the crux one, which is like ten moves, four meters.

Neely Quinn: Right.

Adam Ondra: So first go was to link it as a boulder problem.

Neely Quinn: And that took you four trips?

Adam Ondra: Four trips.

Neely Quinn: So how did you keep your motivated high? How were you like, “I can do this”.

Adam Ondra: [laughs] I think every time I would go for a trip, I thought at least I would link this boulder problem and it never happened. But at the same time, every time it felt so close, so it made me come back. At the same time, maybe at the end of the fourth trip last year, I was like “Maybe this is a bit too hard”, but by then it was maybe too late to give up because I had already put so much into it. Then I decided that I have to train even more specifically, and then I think the very important role was Klaus- my physiotherapist. We came up with special exercises, I was in his office maybe in February. I showed him a video, I explained all the moves which make me troubles, and that was pretty cool.

Neely Quinn: Can you tell me more about Klaus? He is your physiotherapist?

Adam Ondra: Yes.

Neely Quinn: Can you tell me what he does for you?

Adam Ondra: So I haven’t been injured since we were together, so he is helping me to stay injury free, but not only that, helping me climb harder. We just focused on the Project Hard, and I was explaining what the move is like. He is a really good climber himself, so he can really realize, or imagine what is necessary to do the certain moves. We were discussing maybe I can do this move in a slightly different way, and in May we would go here together, and he would watch me climbing it and trying it in real [life]. Together we just came up to a slight change of beta, and for three different things we came up with special exercises.

Later on I found out that kneebars are all about the power in the calves, as long as I am hanging upside down like a bat. So we were focusing so much on the calves, which helped me so much, because all of a sudden I could triple the time in which I could hang in the kneebars. They all of a sudden got so much more comfortable, plus I would even start to make kneebars in places where I always thought they were impossible.

Neely Quinn: Hmm.

Adam Ondra: And then it would be like this move where I turn upside down and have to throw my left foot really, really high above my head. In order to control it better, I was working on my side abs, and that helped me kind of to reach this foot jam in a much more controlled and precise way, which is extremely important. I knew if I didn’t reach this foot jam precisely, then I wouldn’t have any chance to continue to do the next five moves.

Neely Quinn: Right. So in the United States, we don’t use the term physiotherapist. I have a feeling that listeners are probably confused- it sounds like he is a trainer, but also a bodyworker? A physical therapist?

Adam Ondra: He’s actually not a trainer at all, he is a physical therapist.

Neely Quinn: Okay.

Adam Ondra: He has never really done this before, but I think with all his knowledge of the body, and with his experience as a climber, he is the best person to do it, instead of a trainer.

Neely Quinn: Yeah, and the fact that he was out here with you… we were very jealous, first of all [laughs]. How did you convince him to come out here with you?

Adam Ondra: He was excited- it became his own project as well, so.

Neely Quinn: So anytime you are hurt- do you get hurt ever, out here?

Adam Ondra: Yeah, I started the [unclear] since February, so I haven’t really got hurt since we are working together, but for sure. Even has an injury prevention- so we have been working a lot on the stabilization of my shoulders, which I think not only helped me in the project in Silence, but in climbing in general. Maybe one hand dynes, compression things, when it’s like really in full reach, that helped me a lot.

Neely Quinn: Yeah. Can you tell me more about the training that you put in, and do you train on your trips? Or only when you are at home?

Adam Ondra: So if the trips were longer, I would definitely train on the trips as well. The last time we were here for one month and one week, I would be climbing for maybe ten days, then I got a little sick, and I was out of shape. I just started here training in the gym, and putting all the exercises from Klaus. So the Klau exercises mainly focusing on the calves, stabilization of shoulders, and the side of the abs would be in my regular training routine. That would take me about forty minutes every day.

Neely Quinn: Okay.

Adam Ondra: These exercises, during the climbing trip I wold be here and trying to project, I would do it on the second day of the climbing at the end of the day, just before the rest day. That’s it.

Neely Quinn: So you would do it on a climbing day?

Adam Ondra: After climbing, of course.

Neely Quinn: And every second day on you would do that?

Adam Ondra: Yes. During the normal training routine I would do it every day, even during the rest days.

Neely Quinn: That’s a lot.

Adam Ondra: And then I would only take two days off before I would come here, but I definitely feel it was- especially the calves… For example, if I would try the project from the very ground, which before the actual sending only happened once-

Neely Quinn: That is so crazy.

Adam Ondra: So imagine like, there is this first twenty meters up to this biggest kneebar on the whole route- up to there there is a fixed rope hanging. Every time I would either try from this fixed rope, or maybe even a little bit higher. The first goal was to do the crux one, then I would try to do the crux one and link it to the top. Then the next goal was to start two moves in. Then the next goal was to start five moves in. And then the next goal was to do it from this fixed rope, and only then then next goal was to do it from the ground. So like that, I could every time get through the crux one, and at least have some chance. If I would do the crux one and then start trying from the bottom and made it somehow to the crux one, I would have no chance.

Neely Quinn: It’s really unique to Flatanger that you get to use these fixed ropes up there. Is there another place that you can think of where you have that?

Adam Ondra: Um… I would do it in different locations- I wouldn’t just use a fixed rope but maybe aid climb, or climb a little bit up to the point where I wanted to start and take a rest.

Neely Quinn: Honestly it’s a really good idea, if people are in overhung areas, to put up fixed lines.

Adam Ondra: It doesn’t necessarily look nice, but-

Neely Quinn: It doesn’t look great [laughs].

Adam Ondra: The thing here in Flatanger is that some routes actually have jumar starts, because the starts are either impossible, or they are just way harder than the actual route.

Neely Quinn: Right.

Adam Ondra: And instead of back in the old days, someone would glue five jugs close to each other and that would be the start, but I think in that case a fixed rope is a better idea.

Neely Quinn: So going back to your training. We had talked previously about your kneebar training, and you said that this made a big difference. Just to give people an idea what you were doing- I thought it was very interesting to watch you climb, because you would get into a kneebar and you would very quickly go all the way back so you were bat hanging basically. Can you tell me why you did that?

Adam Ondra: So only if I got upside down and bat hang, that’s the only way how all of my body can be absolutely relaxed. For kneebarring this way, all you need is confidence, and you need absolutely no core power- absolutely nothing. All you have to rely on is the calf.

Neely Quinn: Right. And the calves, are you said what got the most pumped, right?

Adam Ondra: Yes [laughs]. So at the end of the route, I would be completely numb in my legs. This part, I was training hard to get my calves as strong as possible.

Neely Quinn: Okay, how did you do that?

Adam Ondra: I would be doing some interval training where I would be standing on the top of my toes, and my knee would be in 90 degrees, so lower with my body, and spend there maybe forty seconds, and then maybe a short rest. Interval training like that. Then I would go into the gym- so I would be doing these exercises in the gym, and then go on the wall and find a kneebar, and try to hang there for as long as possible.

Neely Quinn: Okay.

[laughter]

I’ve always wondered how to train kneebars, I mean…

Adam Ondra: Yeah I tried it a lot in the gym.

Neely Quinn: Do people think- I mean they must wonder what you are doing?

Adam Ondra: Well it’s some kind of semi-private gym, so it’s no problem. Most of the times I would be alone there, and I could change the routes to whatever way I want, so I was all the time there with just screw machine to change all of the volumes all the time. It would be like having different volumes and different kneebars.

Neely Quinn: So this training really helped you stay in the kneebars for long so you could rest for longer? But you still were numb by the end of the route.

Adam Ondra: Oh yeah, because I was going into the complete limit. If I knew I could stay in the kneebar for three seconds longer, then I would do it. Those three seconds longer would give me maybe this extra power for the arms, so I would do the next boulder problem. I was like, conscious about there being a very high possibility of falling out of the kneebar.

Neely Quinn: Yeah.

Adam Ondra: Because I was fighting for every second.

Neely Quinn: I mean, kneebars are also very painful. Not only are your calves getting numb or whatever, but they are painful on your knee. Did you have that experience?

Adam Ondra: I mean a little bit, but with all the modern kneepads it’s not such a big deal. I would like to count it actually, but I think on the actual sending of the route, that took nineteen minutes. I was maybe seven, eight minutes hanging in a kneebar. So that maybe at the end could get a little painful. At the same time, the training helps a lot. The muscles and the skin gets used to it, gets adapted. And of course, also hanging upside down, if you are not used to it, the blood pressure to the head is crazy, but it gets adapted. That’s not really a big deal if you are used to it

Neely Quinn: Really? So in the beginning it was very uncomfortable and then you just get used to it?

Adam Ondra: Exactly.

Neely Quinn: It’s like a totally different level of climbing, I mean obviously.

Adam Ondra: There is still the climbing that you have to do, which is weird anyway, but there is this extra technique.

Neely Quinn: Yeah.

Adam Ondra: Which makes it possible to boulder v15 in the middle of the cave. Otherwise, as I said, if there was no kneebars in the whole route, there would be just jugs to rest, and it’s 10a+ [laughs].

Neely Quinn: So this is 9c. Do you really think that it’s 9c? I mean of all people you would know.

Adam Ondra: I don’t know, I can’t really sure that it is 9c, but it’s my honest opinion. I trained very hard for this route, I think it includes move which fit my style so much- the drop knees, the finger locks, the kneebars. Maybe the fact that it is a roof doesn’t really fit me that much, but I was training hard to compensate it. I’ve done all the 9b+’s in the world- there are three, and they were all first ascended by me. I’m pretty sure this is much harder than any 9b+ there is, and still it took me much longer than any 9b+. Just based on that, that is why I have the courage that I honestly think that this is 9c. I know that saying that this is harder than Change, La Dura Dura, or the other 9b+ doesn’t necessarily mean that it is 9c. It could be just 9b+ hard.

Neely Quinn: Or 9c+.

Adam Ondra: I’m pretty sure that it is not 9c+. I don’t have the level to climb 9c+. But there should be a big gap between 9b+ and 9c, otherwise the grade can be objective. The harder you go in the grading scale, there specific the climbing becomes, and every climber has his strengths and weaknesses. I am aware that there is a big gap in-between 9b+ and 9c, and I know that there should be a gap. Still, I have the courage and this is my honest opinion that this is really 9c, but let’s see. There is always danger that someone maybe finds a different beta. On this route maybe it is possible because it’s so weird and the features when you are there for a first time, you’re wondering “What the heck is this?”. For sure, if I knew the perfect beta that I have now, I wouldn’t have had to invest the first three trips plus here. But that’s part of the game, and it’s fun.

Neely Quinn: Like the Dawn Wall- did you get beta from those guys?

Adam Ondra: A little bit, yeah. It helped, for sure.

Neely Quinn: Do you think that anybody will repeat this?

Adam Ondra: I have no clue. I think not so many people will be attracted because of the style. Not so many people maybe are attracted by fingerlocks and huge drop knees and stuff like this, which I mean, I think the line is pretty okay. The climbing is just weird, but amazing at the same time, and part of the reason why I was so psyched for it. Of course maybe now I am more psyched to change it up for a bit, and maybe use some crimps as hand holds, just for a change [laughs].

Neely Quinn: That would be nice [laughs].

Adam Ondra: On the whole route there are maybe two crimps.

Neely Quinn: Really?

Adam Ondra: There are some sidepulls, some holds I crimp which are not really crimps, but it’s mostly slopey holds, or cracks or fingerlocks.

Neely Quinn: One thing I noticed about your climbing is that you climb very quickly. Why do you do that?

Adam Ondra: After so many years of climbing and so many years of deliberately trying different styles and pace, speed of climbing, I just found out that in most cases that is the most efficient for me. I developed this climbing style which is risky, for sure. In terms of competitions, if I go into the final route, I consciously take a lot of risk. Not that I would kill myself, but that I would slip, or underestimate a move or something like that.

My body works like this- for example, I am very bad in deadhangs. One hand, two hand deadhangs, I can’t really stay there for much time. My climbing- as I climb, I can try hard with one hand, and the other one is completely relaxed. I can tension one arm, and one I can relax for the other arm, and then the other way around, and then the other way around, and then the other way around. At the same time, I developed this climbing style which is quick, but relatively relaxed, or I can stay relatively relaxed. If someone [unclear] they deliberately try to climb fast, they just waste a lot of power. But I think I am very good at staying on this balance where the climbing is fast, maybe my climbing is powerful, but because of the overall time that I spend on the wall, I don’t really get tired, even though I might do some moves in a really powerful way.

Neely Quinn: Yeah it’s very efficient. I mean, it seems like it might be the future of hard climbing.

Adam Ondra: I think, especially if you are working on a project, that you can stay forever. I mean even Wolfgang Gullich back in the day was talking about the future could be in this series of perfectly precise movements, where you could gain momentum from the previous move. So then the actual ascending would be non-stop. The question is when re you ever going to clip, but on some routes you don’t really have to clip, as long as you are high above the ground [laughs].

Neely Quinn: Right, yeah. So speaking of speed climbing actually, one of the questions I wanted to get to was abut the Olympics. Can you tell me your thoughts on the Olympics?

Adam Ondra: It’s great that climbing is an Olympic sport, but the format is very sad [laughs].

Neely Quinn: Okay, that’s where I was going with that [laughs].

Adam Ondra: I’m not really saying that because I would be so bad in speed or I haven’t really tried it much. I just don’t like it- for me, it has nothing to do with climbing. If you go for the competitions in climbing, professional routesetters are putting so much effort into creating something beautiful, something great to climb on, something great to watch. Speed routes are still there, still the same, and you are like, training at home on the same route, and then you go across the whole globe, and you still do the same route- plus the holds are not nice.

I mean, for me the beauty of climbing as well, every climber has his own style. My style is to climb fast, but I have absolutely no reason to call myself a better climber that I can climb a route faster than somebody else. For example, I absolutely disagree with that even in lead, if there is a tie, if you fall on the same move or if you reach the top, the faster wins. To me, it doesn’t make any sense. Now even in the finals of the lead World Cups, there is only a six minute climbing time, which for the short, slow climbers is devastating. I admire the slow climbers. Even if I trained like a horse I would never have the endurance that I could climb that slow, because I know I wouldn’t climb as good.

Neely Quinn: So if you were asked to compete in the Olympics, would you do it?

Adam Ondra: Yes. I think it would be stupid not to, but I disagree with the format.

Neely Quinn: Yeah, yeah I hear you.

Adam Ondra: My goal is to train as much as possible for lead and bouldering, and speed… I would be stupid not to train it, I will train a little bit, but I’ll just do the essential amount of it [laughs].

Neely Quinn: Right, right.

Adam Ondra: And still rely on the good results in the lead and bouldering.

Neely Quinn: I asked one Facebook if people had questions for you. A lot of people want to know the answer to this question: your body has changed quite a bit. You were smaller, back in 2013. I think that can happen naturally, is that what happened with you? Did you try to get bigger?

Adam Ondra: No, no. I think it just happened naturally. My dad wasn’t climbing that much when he was my age, and he is muscular, even more muscular than me actually. For me to stay as lean as I was naturally when I was 16, is almost impossible. It would not be healthy. Still I don’t feel that I climb worse, and even back then, when I was 16 and I really lean and skinny and with no muscles, I still didn’t have endurance [laughs]. Even now, I am much heavier, much more muscular, and I feel like I am much stronger, and the endurance is kind of the same.

Neely Quinn: Really? Because that’s what people want to know- if your weight to strength ratio changed?

Adam Ondra: I am so much stronger on the campus board and stuff like this. In bouldering, maybe, not maybe. Even on just pure crimp problems, and I have boulder problems back at home where I can measure it- even on a crimp problem, where you could say that it is so much better to be lean and skinny, I can still do these boulder problems much easier now that five years ago.

Neely Quinn: Oh. Did something change about your diet at all?

Sorry for the interruption here, but unfortunately I lost part of this recording. I don’t know what happened, but this part about where he talked about his diet just got lost from the records. I wanted to recap what he said, as opposed to just scrapping this whole part, because I thought it was really interesting and informative.

I asked Adam about his diet, and he described what he eats as a lot of nuts and seeds, he eats a lot of grains, he eats a lot of vegetables and fruits. The main difference that he said between his diet now and his diet a few years ago is that he figured out that he needs more protein. Instead of eating fish two times a week like he used to, he is now eating fish once a day. I asked him what he brings up to the crag with him, and he said just basically those things. Nuts, seeds, grains, vegetables, sometimes some fish. He said that food is very important to him, obviously, it’s important to all of us. He said that he has a large appetite, and so the amount that he eats as a opposed to the amount that he could eat is very different, and that’s how he stays lean. That’s where we ended up here, and this is where we will lead into right now.

Neely Quinn: So you do limit the amount that you eat?

Adam Ondra: I mean, as I said, the balance in between feeling okay, not hungry, and feeling totally full for me, the gap is huge [laughs].

Neely Quinn: Right.

Adam Ondra: For me, if I want to, I can eat a lot. And then of course, I might feel heavier. But at the same time, I don’t starve.

Neely Quinn: You’ll just maybe be a little bit uncomfortable sometimes?

Adam Ondra: Yeah, maybe. But for me it’s also depending on the style of climbing I’m training for. For sure, if I am going to the lead World Cup, I know that being two kilos lighter will help a lot.

Neely Quinn: Oh okay.

Adam Ondra: But if I go bouldering, being two kilos less I don’t even have the same power.

Neely Quinn: Really? Okay. So I was going to ask you about that too, because you did Arco. You did pretty well, and so how did you train for that, or did you? Did this just lend itself to training for that?

Adam Ondra: No, no no. Before going to this trip, I was training exclusively for the Project Hard. I was dong campus board, bouldering, and interval bouldering. So doing some boulder problems and then short rest. I never really did more than fifteen moves in a row.

Neely Quinn: Okay.

Adam Ondra: And then I went straight into Arco, also because of sponsor duties. I expected to do really bad.

Neely Quinn: Oh.

[laughter]

Adam Ondra: Because I deliberately didn’t lose those two kilos, because I knew it wouldn’t be so good for Project Hard, and I knew training too much endurance wouldn’t make my training for Project Hard as efficient. In the end, I was so strong that I didn’t really get that tired, because the moves felt so easy.

Neely Quinn: Okay [laughs].

Adam Ondra: But definitely the endurance was limiting me a lot. And it was kind of nice to see because I knew with a little bit of training I would do so much better. I placed second, but I would say there were so many good climbers that messed up during this competition completely, so maybe the second place was not really the real proof of my level.

Neely Quinn: Right, right. How would you have trained differently if you were just training for Arco?

Adam Ondra: Do less bouldering, a little less campus board, and much more fifty move circuits.

Neely Quinn: Fifty moves instead of fifteen?

Adam Ondra: I would still do a lot of enduro bouldering, I think that’s really helpful. But then every second day would be fifty move circuits, the other day would be like thirty five.

Neely Quinn: Mhm. Okay. So you’re still here for a little bit. How much longer are you guys going to stay?

Adam Ondra: We are staying about one week longer, maybe something more. Nine days.

Neely Quinn: Now what?

Adam Ondra: Then going back home, we stay a little bit at home. I have a few projects close to my home, which I am quite psyched about. They’re quite bouldery as well, so I think I can take advantage of all the power I have now. And there are still some projects even here. Hopefully I can finish off this one project that I am trying now until we come back home.

Neely Quinn: This one hear?

Adam Ondra: Yeah, it’s just a variation of Change, that I call Exchange. I think it’s going to be 9b+. It’s very short, it’s only twelve meters. It’s not the most amazing line, but it’s hard. I’m very happy that I can take all my kneebar skills into this route.

Neely Quinn: Right.

Adam Ondra: So I actually found two kneebars in Change itself, which I had never realized before. Hopefully it didn’t get that much ridiculously easier, but a little bit [laughs].

Neely Quinn: And then when you go home, what are you working on there?

Adam Ondra: I must say that maybe this autumn I would just like to take it a bit easier, because I just took so much effort for this project. I would not maybe have a 100% as strict training regime as I normally have for competitions or a project like this. I would spend autumn climbing, and occasionally training, and then climbing. Maybe this project close to my home will be maybe a bit harder than I expect, and then it will force me to train [laughs]. Let’s see.

Neely Quinn: But you feel like you want a break right now?

Adam Ondra: I don’t feel like I want a break- on the opposite side. I’m kind of feeling free and I want to climb as much as possible, that’s pretty much it.

Neely Quinn: But maybe not quite at the level of 9c?

Adam Ondra: Just a step lower I would say [laughs].

Neely Quinn: Because you recently got done with University, right? And so what are your plans now?

Adam Ondra: I mean, just climb as much as possible. Since I got down from the Dawn Wall, my media exposure just changed so much. Back home, before the Dawn Wall, I was like Mr. No One. Of course I was famous in the climbing community, but nobody except for climbers knew me. Now things have changed, and the duties as well. So now I have a manager, and PR assistant, and they are doing a lot of work for me, but still I’m definitely busier in terms of journalists and sponsors. Of course I am trying to have the balance, but now with all the duties that I have, it will be difficult maybe to go back to school. I only finished my bachelors, it would be nice maybe at a certain point to do the master’s. At the same time, with the manager, we’ve got so many exciting projects that I have to be kind of involved, even though he does a lot of work for me, I need to focus on certain things.

Neely Quinn: Are you willing to share what any of those projects are?

Adam Ondra: The project of our Project Hard- Silence- which is probably going to be called Silence anyway. We’ve got a lot of ideas, which for the example, an exhibition from the Dawn Wall, which could be displayed in many different places, where a really broad audience would see it. We are talking about parks in the big cities, or shopping centers, or shopping malls, stuff like this.

Neely Quinn: Oh.

Adam Ondra: So we are in a preparation for all of that.

Neely Quinn: That’s different.

Adam Ondra: It’s just a nice thing to do, like a nice way to promote climbing. I think that’s kind of responsibility I feel in a way, right now.

Neely Quinn: I was wondering about that. We are here in Flatanger, and there’s not very many people here. Apparently there have been more and more- but how do you feel about promoting climbing and making these areas that you love busier? How do you feel about that?

Adam Ondra: I’m very happy to do it for Flatanger, because it’s the climbing area with which I have the most emotional relationship with, except for maybe my home climbing area. At the same time, I think this place is never going to get too busy, which for certain areas is a problem. Let’s say for example, Climb Flatanger gets maybe a little busy in July, but for the rest of the season it’s just so calm.

Neely Quinn: Yeah, it’s actually surprisingly calm for how much media attention it’s gotten.

Adam Ondra: Probably the biggest reason is that it’s much more expensive for Europeans to travel here to Norway than going to Spain, for example, or France.

Neely Quinn: Mhm. Okay. I know that people are probably going to want more details on your training. They are going to want to know when you are actually training at home, how many days do you train a week, how much rest do you take, all these things.

Adam Ondra: I would say my training is quite hardcore, but at the same thing that is not something I would not recommend to most climbers. When I train hard, I usually train six days a week. I would usually have Friday rest, and from Monday until Thursday would be hard training days, and Saturday Sunday, if the weather allows, I would climb on the rock.

Neely Quinn: So you are training Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, resting Friday, climbing Saturday and Sunday.

Adam Ondra: That would be like my average week when I would be in a training period.

Neely Quinn: Okay. Do you get tired?

Adam Ondra: Of course I am tired.

[laughter]

Neely Quinn: And you don’t get injured? That’s a lot of climbing and training.

YAdam Ondra: es. At the same time, the more you train, the more you are adapted.

Neely Quinn: Yeah, that’s true.

Adam Ondra: And then if you have this certain training, if you have this volume, your body is just much more resistant. If you just start training hard and trying to do really extreme moves without having any volume, you’re so much more likely to get injured.

Neely Quinn: So leading up to this particular trip here, can you tell me what you would do on your training days?

Adam Ondra: It would depend on what time of the year. For example, I would start in January and do a lot of volume in January. Just before going to a trip to Spain in February, I would maybe cut down the volume a little bit. Then I would have some trips in spring, but still keeping the volume relatively high. Then before my first trip in May, I would cut down the volume again, focusing much more on the bouldering. As my trips in February in March were more in the climbing areas in Spain where I would need a lot of endurance, so I would still focus more on endurance. In the summer I would cut much more of the endurance and focus more on the bouldering part.

Every single day I would similar things, which would mean every single day I would still have a campus board, I would still have bouldering, I would still have something more endurance based. But in the weeks just before the Silence, I wold only do the interval training instead of fifty move circuits.

Neely Quinn: Are you are doing all this on a bouldering wall?

Adam Ondra: Yeah, exactly. I’ve got two different campus boards in two different places. I mostly train on one training wall, one small bouldering gym where there are no set boulders, just a bunch of different holds on the wall. Every single day I would just figure out my own circuits and my own boulder problems. Sometimes I got training onto the rock, at the home climbing area which is maybe ten minutes away. Especially for the bouldering it’s pretty amazing, because most of it is really steep limestone, physical. What I don’t like about modern gyms with set boulders is that it’s not very… like, the boulder problems are usually six moves, but moves where one of the moves is hard. At my home gym, it’s very easy to figure out a boulder problem which is six moves long and every single move is hard, and it’s much more training efficient.

Neely Quinn: Do you ever get bored doing that?

Adam Ondra: Bored, no. Sometimes I feel tired. Tired, because I have been training so hard, but not really tired of the climbing.

Neely Quinn: Uhuh.

Adam Ondra: Sometimes I feel more excited maybe to go outside, and that’s why I go training outside.

Neely Quinn: Yeah.

Adam Ondra: So I would go onto the rock and just repeat all the different boulder problems, and it’s just so easy because it’s a cave, or part of the wall, where I would just do one boulder problem, move my pad two meters away, and there is another one. In one sector it’s like maybe thirty, forty different boulders between v9 to v13, or v14. If I know all the boulder problems really well, I can really do a lot within a one hour session.

Neely Quinn: So what would you do if you were doing an endurance session on that kind of thing?

Adam Ondra: It would be either interval training, so I would do v9s four times in a row, short rest, do it four times, longer rest, and repeat all of this four times. So like 4x4x4. Or I would- the idea also with my coach, Paxti Usobiaga, is to make relatively short training sessions, but with decent rest in between. For example, my campus board session, would never really take more than forty minutes, plus some warmup. In total maybe it is one hour and ten. During those forty minutes I would do a lot, and get really tired. But in that moment when I finish the training, I feel really tired, but I only need three hours to rest and then I kind of feel fresh again. Whereas if I went into the climbing gym on a rope, or for example doing the endurance circuits, I would maybe have fifty move boulder circuit, I would do it eight times with only two minutes rest in between. So in forty minutes I would be done.

This is definitely a very hardcore session, and you get to climb a lot, like eight times fifty moves, that’s a lot of climbing. I definitely feel completely wasted after that. But it’s this kind of fatigue that from the intensity, but as long as it’s short, I don’t feel tired in a long term. If I would stay in the gym with a rope, and I would stay there five hours, and in those five hours I would climb eight routes, I would feel much more tired because it just took so long.

Neely Quinn: Right.

Adam Ondra: So short training sessions, multiple times a day, with decent break in between, that’s the best. But it takes a lot of time [laughs]. That’s the best, to live in a climbing gym or to have a climbing gym at home.

Neely Quinn: So you are still training with Patxi?

Adam Ondra: Yes.

Neely Quinn: And he helped you with this project?

Adam Ondra: Yeah, we discussed the training programs.

Neely Quinn: So it’s campusing, intervals, it’s some endurance, bouldering, power.

Adam Ondra: And a bit of general fitness training, like TRX or training on rings.

Neely Quinn: And anything else?

Adam Ondra: Maybe in the very beginning of the season for a lot of volume, I would do assisted pull-ups. Like with a rubber band, maybe doing thirty pull-ups in one push, short rest, again, again. That’s just to get the volume in the body so that once you start with hard power training you don’t get injured.

Neely Quinn: Right. To activate your body.

Adam Ondra: Yeah, that’s usually what I do after a two week period of rest, which I always take annually in December.

Neely Quinn: Two weeks?

Adam Ondra: Two or three weeks, depends.

Neely Quinn: What do you do?

Adam Ondra: It’s usually Christmas time, so it’s not that difficult not to climb. There are different things to do. But for me, it would be almost wiser to take a break in the summer, but it’s hard.

Neely Quinn: So you think that you could have taken a break this summer, or this summer would have probably been-

Adam Ondra: Since I had Project Hard in my mind, it was kind of hard to take a break. Because for me, to take two weeks off, it takes a lot of time to get back into shape. In the long term it’s very important, but I know if I take a rest, then for the next month I am very bad.

Neely Quinn: When we talked last, you didn’t really have much interest in weight training. Or like weightlifting. Is that still the case? Do you do any of that?

Adam Ondra: No, no, I don’t think it’s that useful for climbing. Like look at the Japanese. They are just dominating the competitions, and they are really good [unclear] climbers as well. They don’t really do that much physical training, they just mostly climb, climb a lot. They climb a lot on different routes and different boulder problems, and they climb together. That’s the most important in the end, I think. In my training, even though I do a lot of campus boards and a lot of circuits, still very high quality bouldering sessions are very crucial for anyone, even for boulderers, even for lead climbers.

Neely Quinn: I haven’t heard you mention a fingerboard. You don’t do fingerboarding, right?

Adam Ondra: Let’s say I might do one arm deadhangs, but not necessarily fingerboarding using two arms. I don’t feel that my finger strength, that I need it.

Neely Quinn: You think it’s pretty good already?

Adam Ondra: I still train my finger strength, but I train it by bouldering. I feel I either put a lot a lot of weight, or I have to use crimps that are so tiny and so painful that it just ruins my skin. Then my bouldering session is not as high quality because of the skin.

Neely Quinn: So you have tried doing it, and did you not see much of a difference with it?

Adam Ondra: I’ve always struggled with the skin, and my skin in general is pretty good. I think on my level of finger power, I either have to use just so much weight, which even if I take a decent crimp it still feels like I cut my skin half way through, or I would just use no weight on such a tiny crimp that I would maybe do it once, and then if I continue I will make a split.

Neely Quinn: Can you briefly describe any finger skin maintenance that you do to help keep everything good?

Adam Ondra: It depends. Sometimes I have sweaty skin, sometimes it’s dry. When it’s dry it’s a lot of sandpaper, and just some greasy cream. When my skin is sweaty, just some regular climbing treatments that everybody uses.

Neely Quinn: Yeah.

Adam Ondra: I don’t really have any favorite brand. I think I try different ones from time to time.

Neely Quinn: So nothing special.

Adam Ondra: Not really.

Neely Quinn: Okay one of my last questions is about the pressure that you must feel when you are climbing, especially on something like this, which is the first 9c. Can you tell me how you deal with that?

Adam Ondra: It’s hard. The more you sacrifice for something, the more pressure you make. I was pretty lucky to send it so early on this trip, because if it didn’t happen this early, then the pressure would be so much higher. The day when I did it, I had low expectations and low pressure. For me, it’s a lot about visualization, so I would visualize the route over and over again, so I feel more confident that I know it perfectly. Then I would visualize, right before the climbing, I would visualize climbing the route and feeling strong about it.

Neely Quinn: Mhm.

Adam Ondra: Especially if I know the day before I was just climbing it, and I just felt so strong, and I was really close. I just visualize it in my mind, and that kind of helps me to get into this psychological state of mind, where I just don’t think. I switch on the auto pilot and I go. If it’s an onsight, it’s very similar, even though it’s just that I let my experience and intuition make the decisions.

Neely Quinn: Okay.

Adam Ondra: But sometimes it happens, sometimes it doesn’t happen. The more important route it is, the less likely it is that it will happen.

Neely Quinn: I mean, when you were up there sending Silence, and you’re at the last moves, and you could still fall, there’s this huge pressure. What are the things that you tell yourself to make yourself calm down?

Adam Ondra: So it depends. For example, on the Silence, those moves are so easy that I was climbing with 100%-

Neely Quinn: Confidence.

Adam Ondra: No- I was very, very focused. Those moves are so easy that I made sure that in every single move that nothing can happen. Waisting a lot of power, but I know those moves are so easy that I can’t mess up. If it was at the actual limit, then of course I would have to be a completely different climber. I would have to climb the same way that I am climbing through the cruxes.

Neely Quinn: Right.

Adam Ondra: That means taking a lot of risk, and just going for it, and thinking about nothing. Just letting my intuition and experience guide me through the moves.

Neely Quinn: So when you are sitting in the last rest, and you have the to think, like, “Don’t mess this up”, or negative things-

Adam Ondra: For example, there is a jug five moves below the top, and there is like a 6c boulder problem, like v5 or something, super easy to get to the anchor. I was always thinking that if I ever get to this jug, I would be already celebrating. But I was just still so focused and so composed [laughs].

Neely Quinn: So do you do anything to keep yourself composed?

Adam Ondra: No, I think it would be so much better if I just relaxed, because nothing could happen, but I still didn’t want to let anything happen [laughs], which was surprising. So many times when I know that the route is done, I just relax and I just climb easily to the top [laughs].

Neely Quinn: You seem like a very optimistic person.

Adam Ondra: I think so, I definitely consider myself optimistic. I think it’s a very wrong attitude to live with, to be pessimistic. If you always think about the bad things that can happen, it’s very likely that those things will happen. The reality is- what is reality in the end? It’s how we perceive it, and it’s up to us and how we want to perceive what’s around us. I think in the end, if we want to be happy we will be happy. For sure bad things can happen, but it’s up to us as to how we deal with that.

Neely Quinn: Would you say that you are happy?

Adam Ondra: Oh, 100%.

Neely Quinn: Yeah? Especially now [laughs].

Adam Ondra: No, but in general, I’m a super happy person. I’m so glad that I have the opportunity to live how I am, and be surrounded by the people that I love.

Neely Quinn: That’s great. Congratulations on all of your successes- I hope that we hear about you soon again. But I do hope that you take some time to enjoy this also [laughs]. Any final thoughts for people?

Adam Ondra: Go outside and enjoy!

[laughter]

And find the right challenge. Be happy with your climbing, and if you just enjoy climbing a level below your limit, you’re fine. You’re actually a happy person [laughs]. I still enjoy climbing easier routes, but for time to time I need a challenge. That makes me also happy. Sometimes struggling to find the right balance, just focusing too much on climbing hard, and forgetting how climbing is beautiful. Immensely beautiful.

Neely Quinn: It is. It’s funny, because we can say to people “Find you Dawn Wall”, and you actually did find “The Dawn Wall” [laughs].

Adam Ondra: But there is much more in my mind [laughs].

Neely Quinn: Well thank you very much again, I appreciate.

Adam Ondra: You’re welcome.

Neely Quinn: Alright, I hope you enjoyed that interview with Adam Ondra. You can find him online at www.adamondra.com, and he is also on Facebook and Instagram pretty regularly, so it’s easy to follow along with his new projects, how he is training, and all of that. If there were questions that you had that I didn’t ask that were pretty obvious, or if I missed big things, I apologize. I’m not going to lie, I was a little nervous for this interview with him. But, hopefully we got some of the basics covered, and you learned a thing or two about Adam Ondra.

Coming up on the podcast, I will do another interview with Paige, not before I leave in the next couple of days, but I’m going to follow up with her. I mean- unless she sends tomorrow, which is a distinct possibility. We will follow up with her though on her process of projecting Odin’s Eye, whether or not she sends. Other than that, I’m going to be hopefully talking with Charlie Manganello, who is Steve Bechtel’s right hand man over in Lander at their gym. I’m also am going to talk to Jared Vagy soon, who has a new book coming up for climbers, talking all about injuries and injury prevention, and how to rehab injuries. That should be really really good.

Lastly, if you want help with your training, you can go to trainingbeta.com. We have training programs that are all laid out for you- you don’t have to think, you don’t have to make anything up for yourself, we’ve done all the work for you. You can do that whether you are a boulderer or a route climber. So training beta.com, thank you for listening all the way to the end. I appreciate your support, and I’ll talk to you next time.

You talk about that Ondra is bigger, that he have added muscle weight.. but you never mention how much he weighs now and how much he did weigh before. Do you know?

Fabian – Good question! One of those that I should’ve thought of in the moment. I don’t actually know – sorry.

Thank you! Youre doing an awesome job! I have listened to all episodes, some many times. Recently started planning a trip to Flatanger after listening to the episodes with Paige. Keep at it!

Thank you! I appreciate the kind words 🙂